Branding Xi: How the CCP creates a professional PR leadership package for the modern era

By Jessica Batke* and Mareike Ohlberg

Originally published as a Web Special on the MERICS website

*This article reflects the personal views of the author and not necessarily the views of the U.S. Government or the Department of State.

—

This web special shows how Xi Jinping’s image as a charismatic leader has been purposefully created by the CCP’s propaganda apparatus. Even though observers frequently interpret Xi Jinping’s media representation as evidence of a uniquely charismatic leader or even a personality cult, Xi’s image is actually the result of the CCP’s new media strategy devised to respond to an ideological vacuum, to show the CCP as close to the people, and to burnish Xi’s international image as a statesman.

By analyzing press conferences, People’s Daily covers, official websites, and new media content, we demonstrate why Xi Jinping comes across as more charismatic than his predecessors despite the fact that his representation and appearances are highly scripted. In fact, the increased, flashier coverage of Xi Jinping gives us very little insight into either his personality or his personal power.

Click here to download the Web Special “Branding Xi” as PDF.

Almost four years after Xi Jinping became General Secretary of the CCP, it has become clear that he is receiving notably different media coverage than his predecessor Hu Jintao. Data shows that mentions of Xi in the People’s Daily in the first 18 months of his term outstrip mentions of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao during equivalent time periods. He appears in selfies, as a cartoon figure hopping up the career ladder or fighting corrupt “tigers” and as a benevolent father figure called “Xi Dada.”

Many in the media and academia have interpreted these changes as signs that Xi Jinping is concentrating all power to himself and that he is building a personality cult. “Emperor Xi,” as some headlines now call him, is supposedly sidelining most of his colleagues in the Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) and is becoming increasingly like Mao (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Xi’s “power” and “personality cult” dominate the headlines

While coverage of Xi Jinping is clearly different from that of previous leaders, we argue that it should not first and foremost be viewed as evidence for a personality cult or power accumulation. A personality cult in the Mao style would entail the socially or politically mandated display of leadership portraits, a near-religious worship of objects associated with a leader, or the use of images of that leader as an informal currency. This is clearly not happening. The question of Xi Jinping’s personal power is trickier, but we will show that looking at media coverage is not a good way to assess his power.

Instead, we will show that Xi’s media representation should primarily be seen as a product of the new media platforms available to the propaganda apparatus, a deep-seated Party desire to modernize and modify its leadership coverage, and a clean slate of leaders to be portrayed. Our findings are based on the comparison of the media coverage of three leadership generations, starting with Jiang Zemin and Li Peng in 1993. The sources include People’s Daily covers, the coverage of events in print media, official websites, new media, and videos of press conferences.

Xi, the face of a CCP rebranding effort

We assess that the CCP has made the strategic choice to put Xi forward as the “face of the Party.” The previous media coverage trend, emphasizing a line of indistinguishable leaders, did not adequately meet the Party’s branding needs in the social media age. Indeed, it appears that the propaganda apparatus had recognized this problem towards the end of the Hu administration, when photos of the entire Politburo Standing Committee walking together at key government meetings—the canonical image of the “collective” Hu/Wen leadership—stopped appearing in the ritualized coverage of the People’s Daily (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The collective power walk. Left, in 1996 under Jiang Zemin, right, the last use of this sort of image at the “Two Meetings” of China’s highest (at least in theory) legislative and consultative bodies in 2010 under Hu Jintao.

A faceless, collective leadership may be good to avoid creating the impression of a personality cult around a single leader, but it also makes it difficult to produce recognizable politicians to act as the face of the government at home and abroad. As an article published on the website of the Cyberspace Administration emphasizes, having a human being that people can associate with is seen as vital to make people accept and identify with the CCP’s policies. In fact, the CCP had already experimented with presenting former Premier Wen Jiabao as a “man of the people” during the last administration.

Improved packaging does not equal a charismatic leader

Careful, deliberate packaging of the Chinese leadership has long been a central component of the Chinese propaganda apparatus. This basic tenet has not changed under Xi, despite the package’s glossier exterior. Xi seems to have very few “unscripted moments” that would give insight into what he is really like as a person. Whether this is the result of his personal preference or the needs of the propaganda system is unclear.

Hu Jintao similarly had very few unscripted moments after ascending to the highest levels of central government, though there is anecdotal evidence that unlike Xi he was very scripted in private meetings as well. Incidentally, this old gala footage suggests Hu was not always as wooden a public speaker as he later came to be known. Like Hu, Xi relies heavily on written notes in public events, and does not convey anything like the charismatic style that some Chinese and Western media coverage attribute to him. Most of the time, he seems either sullen or indifferent.

This contrasts markedly with Premier Li Keqiang. Li frequently makes apparent off-the-cuff remarks at public events and engages actively with his interlocutors and the audience, making his public persona more akin to that of Jiang Zemin and Premier Zhu Rongji. In either case, such footage is an important reminder that Chinese media coverage of the top leaders tells us very little about who these leaders are as individuals.

See for yourself: click here for a compilation of press conference footage of Jiang Zemin, Zhu Rongji, Hu Jintao, Wen Jiabao, Xi Jinping, and Li Keqiang. An extended version is also available here.

New media: the medium sells the message

The biggest change in media coverage—what makes observers feel so different about leadership coverage—is taking place on new media platforms. Xi’s representation in new media is slick, using a “new style” of language. New formats such as cartoons, infographics, video clips, and selfies represent a significant departure from previous leadership coverage, which was restricted to the familiar, narrow range of “old” media formats.

This aggressive move toward 21st-century-style coverage is no accident. The CCP has long realized that its old formats of leadership coverage are not appealing to the younger generation. As early as 2003, the Party Center issued a document to curb reports on leadership activities in sub-national media. In 2012, when the CCP committed to “eight provisions” (八项规定) to improve the work style of the Party and the government, “improving news reports,” aimed at reducing the number and length of reports on leaders’ activities, was one of the items on the list. Importantly, the point is not to report less on leaders, but to cut out the old-style, dull recounting of their activities.

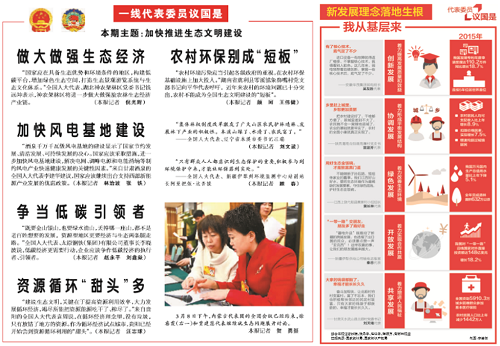

Instead, media and politicians are asked to adopt a new style (新官話, literally: “new official-speak”), different from the empty political speech the CCP had repeatedly identified as a problem under the last administration. One distinctive feature of the “new style” of official Chinese communication is the infographic (图解), first used in the last years of the Hu-Wen administration (Figure 3). These days, anything from a Xi Jinping speech to a government work report will be presented in the form of an infographic.

Figure 3: Infographics on the “Two Meetings” (2010 and 2016).

Source: People’s Daily, Cover page, March 9, 2010 and People’s Daily online.

Part of the “new style” arrangement has been a willingness to experiment with new formats, some of which have been more convincing than others. It has also meant allowing and encouraging a number of bottom-up initiatives – including a number of grassroots (or at least non-central-government) songs and videos devoted to “Xi Dada.” Though some observers view these paeans to Xi as evidence of attempts to create a personality cult, the administration has tried to reign in some of the excesses, even if there is no absolute ban on such images. The CCP is clearly learning how to successfully interact with individually-generated content in a way that preserves its control.

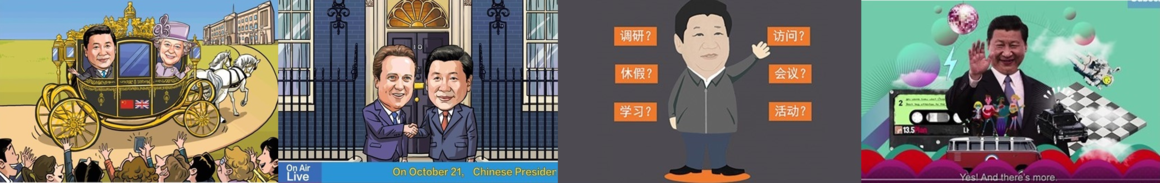

Taking advantage of foreign expertise and a new slate of leaders

As noted above, much of what we see in new media and new formats was previously taboo. In the past, the propaganda bureaucracy only presented leaders (Chinese and foreign) in very restricted, formal formats. Nowadays, both China’s top leaders and foreign leaders can be portrayed as cartoon characters (Figure 5). In producing these cartoons, propaganda authorities are working together with the private sector, including with foreign PR companies.

Figure 4: Yup. The presentation of China’s top leader has changed.

The Chinese propaganda apparatus is also looking to other governments as potential models for shaping leaders’ images. Take,

for example, the General Secretary’s annual New Year’s address, a

staple of the Chinese leadership for decades. The speech was rather

formal under Hu Jintao but has been retooled under Xi. It now has a similar look and feel to Angela Merkel’s New Year’s address, for example, or to Barack Obama’s weekly address.

Figure 5: Hu Jintao giving the New Year’s address from behind a lectern in 2009

Figure 6: We can’t help but notice the convergence in how politicians look when addressing the public

The shift towards new types of media was, to some extent, likely an organic change. The 2012 Chinese leadership transition was the first major inflection point since the explosion of the new media tools that the leadership is now using to promote itself. When Hu took over in 2002, by contrast, no major social media platforms (such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram or their Chinese counterparts) had even been founded, let alone utilized as branding tools by national leaders.

The notion that a leadership inflection point might affect the use of new media is supported by similar occurrences elsewhere. New administrations in the US and the UK, for example, set up YouTube channels for their top-level executive institutions (the White House and 10 Downing Street, respectively). In other words, some updates to the propaganda toolkit would likely have happened with or without Xi Jinping.

Here a Xi, there a Xi, everywhere (in the People’s Daily) a Xi

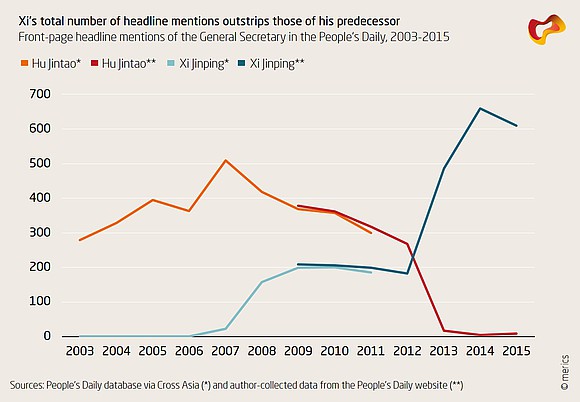

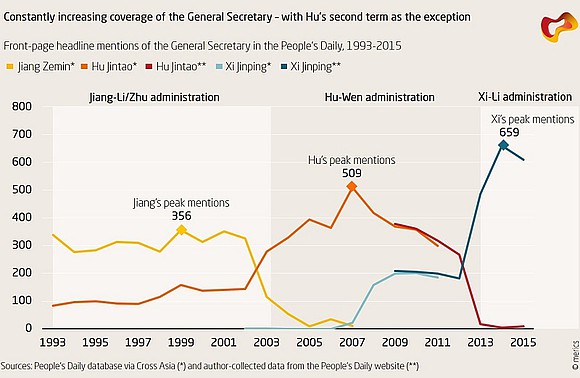

The volume of media coverage about Xi Jinping does indeed represent a notable increase over that of his predecessor. A look at the gold standard of Party media—front page coverage in the People’s Daily—shows that mentions of Xi Jinping have been higher than similar mentions of Hu during his tenure (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Viewing the numbers as part a longer continuum, however, suggests that the outlier in terms of media coverage was the second Hu administration rather than the current Xi administration. Headline mentions of the General Secretary slowly increased over Jiang Zemin’s term, and climbed even faster over the first five years of Hu’s tenure.

In

fact, except for the second term of the Hu-Wen administration, we see a

fairly steady increase in such coverage over time (Figure 8). Had

leadership coverage trends continued over the full 10-year Hu

administration, the number of Xi Jinping mentions would probably not

seem so out of place. Instead, during Hu’s second term, coverage of him

steadily decreased as coverage of most other PBSC members increased.

This is likely one major reason why media coverage of Xi Jinping feels so

different than that of Hu Jintao: the gap between Hu coverage during

his second term and that of Xi’s first term is quite wide.

Figure 8

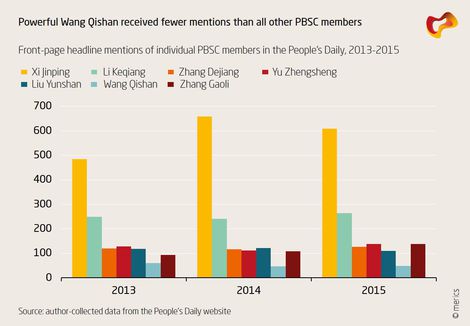

Volume of coverage does not equal power

There are several problems with interpreting these charts to mean that Xi Jinping is more powerful than his predecessors or that he is trying to build a “personality cult.” First, it would suggest that Hu Jintao was more powerful than Jiang Zemin (Figure 8). Secondly, it would mean that Wang Qishan, the PBSC member overseeing the anti-corruption campaign, is less powerful than all other PBSC members, seeing that he only gets about half of the front page coverage of Yu Zhengsheng, Liu Yunshan and others (Figure 9). Most observers would agree that neither of these are the case. Simply put, interpreting the volume of media coverage as directly correlating to a leader’s power clearly does not work.

Figure 9

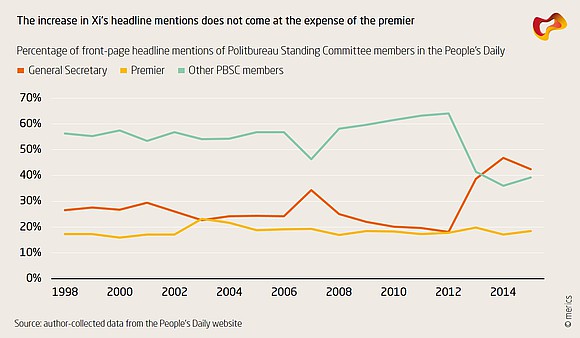

It’s not just about Xi … it’s also about Li

A number of people

have argued that Li Keqiang is being sidelined by Xi Jinping. While

this may or may not be the case, it is not reflected in the share of

official media coverage that Li receives. The percentage of PBSC member

coverage consistently hovers around 20 per cent for the premier.

Instead, the increase in coverage of Xi Jinping clearly comes at the

expense of other PBSC members (Figure 10).

Figure 10

There are a number of possible reasons for this. First, under Jiang and Hu, the PBSC consisted of nine members, whereas under Xi, it was shrunk to seven. Second, much of the coverage of other PBSC members under Hu and Wen went to a few select “mid-layer” people (Jia Qinglin and Zeng Qinghong), who received a significant proportion of coverage. Under Xi and Li, no comparable people exist on the PBSC. Again, this should largely be seen as unrelated to power, given that under Xi, one of the most powerful PBSC members (Wang Qishan) receives the least coverage.

The Premier also gets his own cartoons

While most other PBSC leaders are largely, though not completely, receding into the background, there is one notable exception. In addition to Xi Jinping, the CCP is clearly trying to create a second recognizable face: Premier Li Keqiang. For instance, Li appears as a cartoon character hanging out with German chancellor Angela Merkel or saving the day in crisis-ridden Europe (Figure 11). The English-language website of the Chinese government even highlights quotes by the Premier, the format of which (though of course not the content) is somewhat reminiscent of Quotations by Chairman Mao (Figure 11). Of course, nobody is suggesting that Li is building a cult of personality. He isn’t, and neither is Xi.

Figure 11: Left, cartoon Li Keqiang saving the EU and chilling over a beer

with Angela Merkel afterwards. Right, quotations from Premier Li

Source: news.xinhuanet.com, news.ifeng.com, english.gov.cn

Disaster coverage: Li remains “consoler-in-chief”

In looking at how the media covers the leadership response to disasters, we found that the Premier retains the role of “consoler-in-chief” after major disasters, and that this role has not shifted to Xi (Figure 12). The qualitative changes in coverage for these events in the Xi era are changes of degree, not of kind, and are well within the bounds of normal alterations of coverage that occur both across and within administrations.

Figure 12: The Premier is on the scene. Left, Wen Jiabao after the Wenzhou train crash in 2011 (Source: news.cn); right, Li Keqiang after the Tianjin explosions in 2015.

Ritualized event coverage: leaders move out and the people move in

Aside from the numbers, have there been any significant changes in how the top leaders are depicted in the official media? Xi has certainly made the headlines for being a “man of the people,” eating in small baozi stalls mingling with ordinary Chinese and wooing people with his charisma. But is the people-centric coverage of Chinese leaders really new? Or are we just seeing more of it because the CCP now uses new media to spread its message? Were there similar attempts to show the closeness between the top leadership and the people before Xi Jinping?

In fact, the idea that Chinese leaders need to mingle with ordinary Chinese is not new. The People’s Daily has been trying to show how close the top leaders are to the people. In recent years, the emphasis on the people at important occasions has grown.

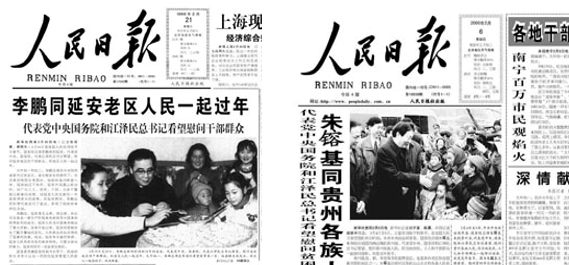

Take, for example, coverage of Lunar New Year. After publicizing the annual New Year leadership meeting, the People’s Daily had, in the past, used the following holiday days to highlight leadership interaction with ordinary Chinese.

This began in the Jiang era, when pictures of then Premier Li Peng showed him celebrating the New Year with average folks (Figure 13). Beginning in the Hu era, the emphasis on leadership interaction with ordinary Chinese increased markedly, with several days of coverage showing images of both the General Secretary and the Premier out among the people.

Figure 13: Li Peng (1996) and Zhu Rongji (2000) meeting the people

Figure 14: Mingling with the ordinary folks: Hu Jintao, Wen Jiabao, and Xi Jinping

Conclusion: A new image for a new era

A

close look at Chinese media representations of the top leader reveals

some changes under Xi Jinping, but there is no indication that the CCP

or Xi Jinping are replicating the excesses of Mao’s heyday. Enhanced

media coverage does not equal a personality cult, nor is it a

particularly effective means to judge a leader’s power.

Instead, what

we are seeing is the purposeful construction of a “charismatic leader,”

primarily to make the Party more relatable to ordinary people and thus

improve the perception of the CCP as a whole. This has happened at a

time when the Party has decided to experiment more with modern means and

channels of communication, which make the changes appear even more

pronounced.

Given the propaganda developments and strategic considerations that predate the Xi administration—and despite significant changes in leadership coverage under this administration—it makes more sense to view current leadership coverage as strategic policy continuity under new tactical circumstances. Nonetheless, the presence of a new leader may have played a critical role in enabling the Party bureaucracy to take fuller advantage of these new media formats.

Looking forward, the 19th Party Congress in the fall of 2017 will be a key testing point for our expectations about leadership coverage in the Chinese media. Based on the overall continuity that we have observed in much of the official Chinese media’s ritualized event coverage, we expect that media representations of Xi and the rest of the leadership at next year’s Party Congress will look similar to—if slightly fresher than—the last few Party Congresses.

But what if there is a dramatic break from previous coverage, such as

a week of Xi-only front pages, or the complete absence of other

leaders? This could signal more profound propaganda changes than we

currently perceive. In this case, we would need to reconsider the aims

of current propaganda trends, perhaps as signalling a dramatic

propaganda break from—rather than just a slick update of—the former

leadership.