Message Control: How a New For-Profit Industry Helps China’s Leaders ‘Manage Public Opinion’

By Mareike Ohlberg and Jessica Batke

This article, including a number of sidebar articles and supplemental materials, originally appeared on ChinaFile. The text below does not include illustrations and charts that are part of the full article.

—

Li Wenliang’s death had only been announced a few hours earlier, but Warming High-Tech was already on the case. The company had been monitoring online mentions of the COVID-whistleblower’s name in the several days since police had detained and punished him for “spreading rumors.” Now, news of his deteriorating condition, and eventual passing, had triggered a deluge of sorrow and outrage online adorned with candle emojis, photos of farewell wishes scrawled into the snow, and a final image of the 34-year-old ophthalmologist as he lay in his hospital bed in Wuhan.

It was February 7, 2020, and Warming High-Tech’s “Word Emotion Internet Intelligence Research Institute” swung into action, drafting a “Special Report on Major Internet Sentiment” for “relevant central authorities.” Warming’s report explained that online discussions of Li had “flooded” the Internet; the public’s “grief and indignation” would demand an urgent response from government officials. The company also offered recommendations for what such a response might entail, including advice that reads very much like public health guidance: “increase support efforts for affected regions, promptly respond to the people’s demands”; “prevention and control measures in non-affected areas can gradually be slowed and business can progressively and orderly resume, reducing losses and negative pressure for everyone.”

At the same time, the report focused on controlling the media narrative, urging officials to “affirm Li Wenliang’s contribution to the epidemic prevention and control efforts” and “increase efforts to quickly identify rumors and [information] with bad intent from foreign forces, clear them up, and shut them down.” In other words, both COVID-19 and the online chatter about it imperiled the health of the body politic. Already, the battle against this new and deadly disease had become intertwined with the battle against unfettered public speech.

The outbreak of COVID-19 presented Warming High Tech’s clients with an especially acute challenge. But the company’s recommendations reflect a widespread set of practices in a new, for-profit industry that has cropped up to help China’s leaders address a more everyday difficulty: the power of the Internet to circulate the thoughts and feelings of China’s citizens.

In official writing on the subject, the problem appears dire. China’s leader, Xi Jinping, speaks of it using the language of war, calling the changing media environment “a great struggle” and exhorting propaganda officials to “grasp the initiative on this battlefield of public opinion as quickly as possible. [We] cannot be marginalized.” Xinhua News Agency, citing Xi’s guidance, described the Internet and new communication platforms as “the main battlefield for news competition, and even more so the Party’s front line for public opinion work.”

Across the country, officials are arming themselves for this battle with a new arsenal of technology and squadrons of human recruits. To better understand the tools and techniques Chinese officials use to stem the tide of public opinion at home and abroad, ChinaFile analyzed some 3,100 procurement notices and corresponding documents, issued by both central and local governments across China and dated between January 2007 and late August 2020. In these notices, authorities express their desire to more easily track, manipulate, or erase online speech through purchases of “public opinion monitoring” software and services. These commercial technologies aren’t intended to replace the monitoring and censorship performed by humans, but to enhance them. The procurement notices also highlight governments’ deepening dependence on commercial enterprises as the sheer volume of online information threatens to overwhelm public sector employees’ capacity to manage it. Together, the documents reveal the breadth of Party and state agencies engaged in this work—not only traditional propaganda organs, but entities ranging from a tax bureau in the southwestern city of Kunming to the Traffic Police in northwestern Lanzhou, from the inspection station at a Shenzhen border crossing to a Beijing government office hosting an international exhibition of horticulture.

Yet, leaders’ anxiety about online speech extends far beyond the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC’s) borders. Earlier this year, ProPublica reported that more than 10,000 fake Twitter accounts were “involved in a coordinated influence campaign with ties to the Chinese government” with the aim of countering negative international sentiment as COVID-19 spread across the globe. ProPublica linked the campaign back to an Internet marketing firm in Beijing, which the state-owned China News Service had hired to enhance its Twitter influence. And just this month, researchers at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute showed evidence of a coordinated campaign to like and retweet content from a Chinese government spokesperson. Twitter, notably, is not accessible in mainland China, so these efforts undoubtedly took aim at international audiences.

Chinese authorities’ outsourcing of work to the commercial sector echoes government practices throughout the world. “There’s a global trend of governments outsourcing,” says Jude Blanchette of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). “One of the priorities of [Premier] Li Keqiang, and of Xi Jinping, is holding at bay the growth of bureaucracies, and cutting red tape.”

But the assistance China’s public opinion contractors deliver extends far beyond merely improving bureaucratic efficiency. Rather, they offer a solution to a vexing conundrum for China’s leaders—and a central problem for any authoritarian state—namely, how to assess the public’s acceptance of their rule without the dangers of allowing citizens to speak their opinions openly.

The Party hopes to harness the commercial sector’s advances in big data and machine learning to understand what Chinese citizens think, respond adequately to key concerns, and siphon away overly critical sentiment—all without members of the public seeing their compatriots’ complaints. The goal is to deliver a minimum standard of responsive governance while simultaneously preempting the very feedback that could help officials govern more effectively. For-profit companies are actively assisting the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as it works to eliminate one of the main threats to its survival: how people feel about, and talk about, the power of the regime itself.

* * *

Public opinion” may be the nearest translation of the Chinese word “舆情” (yuqing), but it fails to capture the term’s full meaning. The CCP brought yuqing into common usage, says literary scholar Perry Link, and it conveys a clear political hierarchy. “It means approximately, ‘expressions among the “masses” (meaning the people we rule) about things, especially things relevant to our rule’.” Of course, not all public opinion toward the regime is critical. Plenty of citizens post content that celebrates national achievements and praises China’s top leaders. But when yuqing appears in procurement documents, it implicitly frames citizens’ independent thoughts and feelings as a kind of ever-present, imminent threat that officials must act upon and deflect. As David Bandurski, co-director of the China Media Project, puts it, yuqing “contains both the notion of ‘public opinion’ and the implications of that public opinion—the whole raison d’être of the monitoring and control industry.”

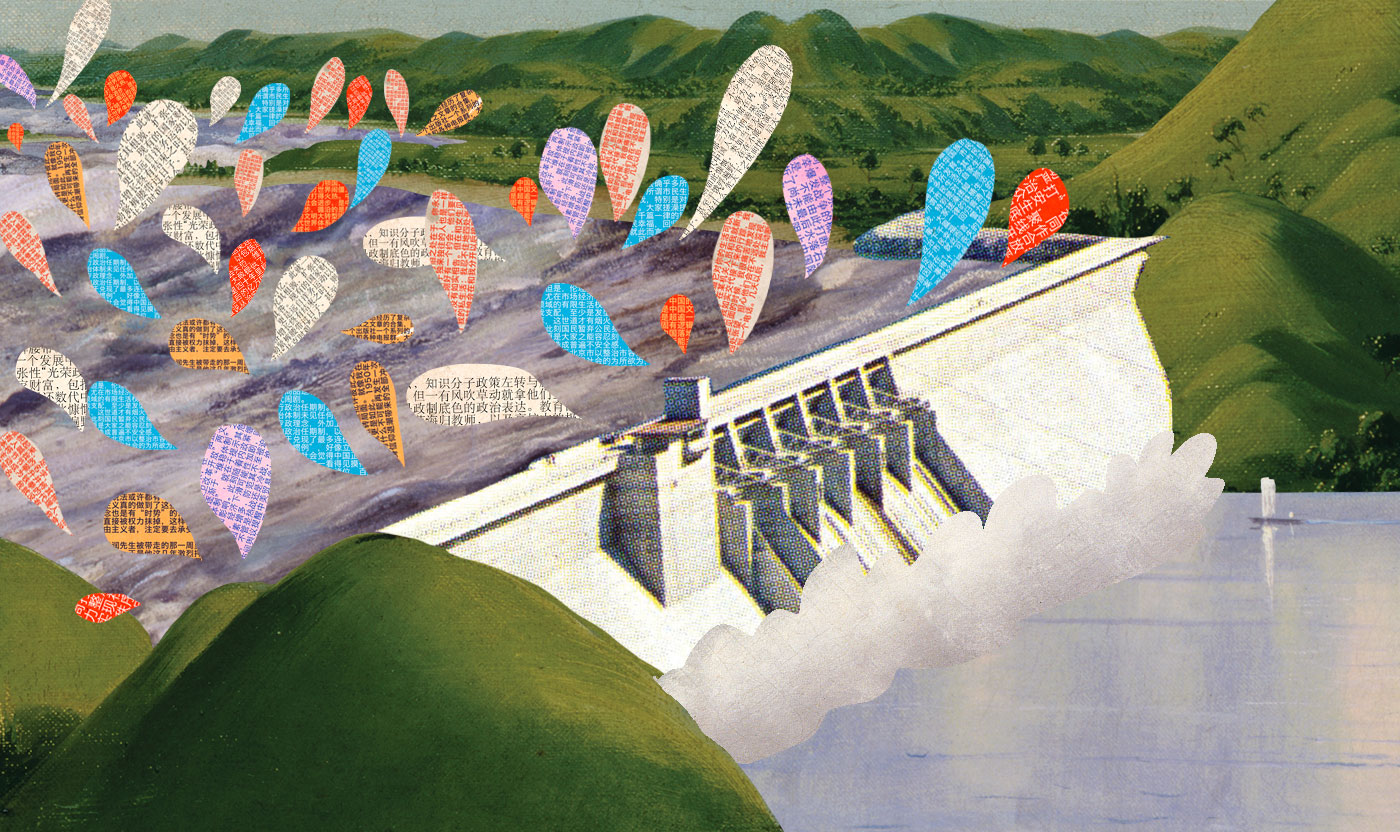

A 2016 State Council policy directive, calling upon local governments to “better respond to public opinion,” lamented the frequent occurrence of “public opinion incidents” in recent years, instances when citizens’ self-expression had burst out beyond authorities’ means of control. Officials around the country, procurement notices show, clearly feel that “guiding” or “channeling” spontaneous, bottom-up sentiment is necessary to avoid such incidents. Bandurski likens the “channeling” process to controlling the flow of water, a “hydrological” approach to managing public opinion that “recogniz[es] the speech act, and its collective power, as a force of nature that must be tamed . . . ‘Channeling,’ then, [is] about harnessing the power of for-profit newspapers and magazines, commercial Internet portals, and social media in order to better inundate the public with information from state sources. Ultimately, [it is] about taming the flood in the Internet age.”

* * *

‘A New Nexus’

In June 2017, the Propaganda Department of Jiayuguan, a city in Gansu province named after a nearby pass in the Great Wall of China, set out to purchase “online public opinion detection software and services” for use by the municipal Cyberspace Administration. “In recent years, negative public opinion about Jiayuguan on the Internet has been increasing by the day,” explained the department’s procurement notice, “and public opinion monitoring departments face difficulties with the large number of websites, the massive amount of information, and with capturing negative information in a timely manner.” The way officials responded to “public opinion incidents” would “determine the direction in which those incidents developed.” Continuing to rely solely on humans wouldn’t get the job done. “So that it can quickly discover and grasp online public opinion information, nipping the hidden dangers of social contradictions and instability in the bud, the city Party Committee’s Cyberspace Administration Office urgently needs [to procure] a set of specialized public opinion monitoring software tools and a public opinion service team.”

Jiayuguan’s propaganda officials could shop around. A range of Chinese companies, including Boryou Technology, Coolwei, and Eefung Software, offer public opinion management services. There are also a number of firms affiliated with various parts of the Party-state, like Run Technologies Co., Ltd. Beijing, which is jointly owned by Addsino and the Third Research Institute of the Ministry of Public Security (in Shanghai); and CYYUN, which is associated with the Communist Youth League. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the country’s major state-owned media outlets appear to be cashing in, taking advantage of their valuable connections to the central government as well as long experience controlling the information Chinese citizens consume. Among companies securing contracts to monitor “key opinion leaders” and display public opinion “hot spots” on color-coded maps, for example, are Beijing People’s Online Network (People Online), affiliated with the Party’s flagship newspaper People’s Daily; Beijing Xinhua Multimedia Data (Xinhua Data), which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of China Economic Information Agency, itself under the authority of Xinhua News Agency; and Global Times Online (Beijing) Culture Communication, owned by Global Times Online. Government agencies sometimes even contract with these state-affiliated firms through “single source” procurement, bypassing a competitive bidding process. Among Xinhua Data’s services to government purchasers is an internal channel that allows local officials to report “major public opinion incidents” directly to central authorities.

To be sure, some of the services Chinese officials purchase wouldn’t sound unfamiliar to international brand management companies like Meltwater, Cision, and Brandwatch. These firms also offer monitoring services similar to some of those sought by local PRC governments. In the China context, however, commercial monitoring services can become extensions of state power, with the authority to bury or remove information perceived as threatening to the regime.

Even without for-profit firms to assist them, Chinese authorities have monitored and manipulated public opinion since the very founding of the PRC. China’s leaders reinvigorated these efforts after the 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square rattled the Party’s assumptions about its popularity and legitimacy. In its organizational reach, and in its control over national narratives and symbols, “The role of the propaganda system in the current era in China is akin to that of the church in medieval Europe,” wrote scholar of Chinese politics and international political influence Anne-Marie Brady in 2006. Beijing’s interest in monitoring was not limited to domestic audiences. The official Party mouthpiece, Xinhua News Agency, has long monitored and summarized foreign media reports as well as penning classified “internal reference” assessments for China’s leaders.

Propaganda work has become even more critical in an era when the Internet amplifies citizens’ voices, forcing authorities to continually adjust and fine-tune their traditional media controls and develop new strategies for digital communication technologies. By 2013, The Beijing News estimated that 2 million government employees were monitoring social media, a figure which did not include all the in-house censors employed by websites and Internet service providers to ensure their compliance with state mandates on permissible content. Through the development of more (and more sophisticated) Internet governance mechanisms in the 2010s, writes Leiden University’s Rogier Creemers, the Party-state “has sought to interlock propaganda and public opinion work with advanced data-gathering and processing techniques.” The blending of technology and propaganda has also spawned “a new nexus between the central state and private enterprise” in which not “all important players in the online sphere are state-owned.”

The existence of this “new nexus” necessitates that the Party-state trust commercial companies with information it considers “sensitive.” It is no surprise, then, that authorities demand a level of secrecy about the work they’re paying for. In 2018, a procurement notice from the Gansu People’s Provincial Government called its “public opinion monitoring system itself a top-secret system.” Some service providers must sign confidentiality agreements when they win contracts, “to keep monitored negative public opinion strictly confidential.” In 2019, the Tiananmen Area Management Committee in Beijing, a body responsible for physical maintenance of the famed square and its surroundings, sought a service provider that would monitor “sensitive information related to the Tiananmen area” in Chinese on “the official web pages of overseas media, hostile overseas platforms, overseas Chinese search engines, and overseas Chinese newspapers.” The Committee specified that the provider must “strictly ensure the security of the technology and the information, and must not allow any leaks or breaches of confidentiality.” These concerns may explain why foreign companies comprise a relatively small portion of the market. They might sell data to Chinese government buyers, but given how rarely procurement notices mention them, it’s unlikely foreign firms play a major role in the system.

Government purchasers also seek assurances that their contractors possess the correct political judgment and understand “sensitive” issues. Multiple procurement notices, using identical language, called for bidders with “a strong ability to analyze and judge sudden and sensitive events, a high degree of political sensitivity, political insight, and political discernment, and rich experience in handling public opinion.” This “discernment” would prove critical because not everything in the propaganda process can be automated; even high-tech monitoring systems require human intervention and management. Thus, officials’ concerns about hewing to political orthodoxy also extend to the individual staffers (such as “Internet Public Opinion Analysts” and “Internet Commenters”) that government agencies sometimes want companies to dispatch as part of a service package.

Earlier studies of or interviews with “Internet Commenters”—sometimes derisively but inaccurately referred to as “50 centers” or the “50 Cent Party” for the amount they supposedly earn for each Internet comment they write—suggest local propaganda departments and Internet monitoring offices directly hire such commenters themselves. Now, however, procurement notices show government officials explicitly itemizing “Internet Commenters” as part of the service packages they seek, suggesting that at least some measure of this work is farmed out to commercial firms.

Employing “Internet Public Opinion Analysts” and “Internet Commenters” through private companies puts an extra layer of remove between the Party and the people safeguarding its propaganda online. Some aspects of Internet monitoring and censorship have long been performed by non-Party entities, such as individual websites and Internet service providers. But this arrangement may still unnerve Party leaders who define monitoring and properly guiding public opinion as among the Party’s most fundamental tasks. Indeed, perhaps as a way to allay these concerns, the central government trains and certifies some of these workers. Since 2013, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security’s China Employment Training Technical Instruction Center (CETTIC) has trained “Internet Public Opinion Analysts” in conjunction with the People’s Daily Online Public Opinion Monitoring Center. Multiple procurement notices contain the term “Internet Public Opinion Analyst,” and two even mention official certification as a requirement. Most government buyers don’t specify whether it is standard for public opinion analysts to also engage in Internet commenting, or whether those are usually completely separate jobs.

The Beijing Traffic Police asked in 2019 for “three or more professional public opinion early warning analysts to carry out reporting and early warning work 24 hours a day, seven days a week, all year, day and night, in order to ensure 24-hour on-duty early warnings. [Analysts] categorize valid information and then screen it, and manually check and report in real time the day’s key public opinion information.” On a 10-person team the State Taxation Administration sought in 2017, three people would monitor major domestic websites for “tax-related public opinion information.” The entire team would work in three shifts: from 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., from 5:00 p.m. to midnight, and from midnight to 8:30 a.m. The Shenzhen General Border Inspection Station also specified shifts for the five workers they sought in 2017, though they only requested regular working hours between 8:00 a.m. and 5:30 p.m., with staff available for emergency response and ad-hoc tasks on evenings and weekends.

Which Party or state institutions find themselves needing for-profit help to track what people are saying online? Propaganda departments—and their close cousins, online news centers and information centers—show up the most often among awarded bid notices, followed by notices from various public security organs. But beyond these obvious buyers, a truly motley set of agencies look for outside help to strengthen their Internet monitoring. Local courts and prosecutors’ offices, hospitals, tax offices, universities, land and resources bureaus, and even the Export-Import Bank of China all purchased public opinion monitoring systems of some type between 2007 and August 2020. These buyers are most interested in their own parochial concerns, namely, the public’s opinions of them and of the latest news relating to their work. The Institute of Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine at the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, for example, wanted to conduct round-the-clock monitoring of information related to the safety of traditional Chinese medicine. In Lanzhou city in Gansu province, the Traffic Police sought “seamless 24-hour monitoring of the entire Internet” for online chatter mentioning their office. The Shenzhen General Border Inspection Station solicited a system that would scour Hong Kong and Taiwanese media for “negative public opinion” related to the station.

The diversity of these purchases also reflects the piecemeal nature of Internet monitoring in China. With few exceptions, centralized systems for sharing data between different government bodies do not yet exist. Moreover, the highly specific kinds of information buyers want to monitor would make most data-sharing largely useless anyway. In Beijing, for example, about 40 different Party and state offices have each sought their own monitoring systems.

Yet, some localities may still seek to pool resources into a single warning system that notifies different parts of the bureaucracy when something untoward pops up online. In 2019, the Propaganda Department in Liucheng county, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, wanted to build a “public opinion general monitoring system” that could cover the entire county. Tracking activity on major news media, public WeChat accounts, Sina Weibo, Toutiao, TV, blogs, forums, and another 80 million sites, including other social media, the system purports to “solve the public opinion monitoring needs of all departments in the region.” The system also allows for “competition analysis,” which ranks different departments in Liucheng according to their favorability with the public.

The diverse roster of buyers results in part from central-level instruction. In explaining why they need to purchase a public opinion monitoring system, some officials invoke speeches by Party leaders and Party documents, including the “Notice on Better Responding to Public Opinion on Government Affairs in the Course of Open Government Affairs Work,” issued by the State Council in 2016, and a February 2019 article by Politburo member Cai Qi in which he called on all districts to pay more attention to public opinion. The 2016 State Council missive instructs government agencies at all levels to establish public opinion monitoring and response mechanisms, essentially mandating a fragmented system in which departments can be evaluated based on how well they keep public opinion on course.

But local authorities likely have other motivations for seeking personalized support from the public opinion services sector. “Citizen complaints tangibly affect bureaucrats’ career security,” writes Iza Ding, Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Pittsburgh. “Although civil servants are mostly disciplined by internal bureaucratic rules, public opinion often plays a decisive, and sometimes capricious, role in their fate, which makes public scrutiny a crucial driver of bureaucratic behavior.” The political system also rewards those who can prevent negative information from reaching Beijing. Though botched cover-ups can torpedo a career, keeping local problems local is a tried-and-true way for officials to protect their jobs. As the array of platforms Chinese citizens can use to air grievances has grown, so too has the range of tools authorities seek to stop discontent from leaking out and reaching either the broader public or their superiors in Beijing.

Additionally, officials function in an ecosystem in which they compete for promotions. In his work on local governments’ big data collection and public service provision, Christian Göbel, Professor of Modern China Studies at the University of Vienna, has found that government offices rarely share data with one another. Sometimes, this is simply due to institutional inertia. “It’s just fragmentation. It doesn’t go out of fashion,” he says. But individuals within these institutions often lack incentives to actively assist counterparts in different departments. People working in propaganda departments, for example, are “competing with people working in public security and other bureaus” for promotions, Göbel says. “It’s not in the interest of the propaganda department to help them.”

At bottom, though, it is the underlying power structures of the Chinese state that demand even low-level, specialized government offices assess and redirect public opinion. “It’s very much in line with the whole Marxist-Leninist communications theory of it all—the ‘mass line’,” says Blake Miller, Assistant Professor at The London School of Economics and Political Science, “the whole idea of leaders’ going out and gathering the thoughts of the people that are chaotic and contradictory, and systemizing them and retransmitting them back to the masses to limit the confusion in their thoughts and create harmony.”

* * *

‘5,000 Sensitive Weibo Accounts’

In 2017, in the city of Fuzhou, which sits on China’s southeastern coast just across the strait from Taiwan, the municipal Propaganda Department drew up a list of the public opinion topics it wanted to monitor:

Type A InformationType B Information

- Information about persons or incidents requiring attention;

- Interpretations and evaluations of policies or measures issued by the municipal Party Committee or municipal government;

- Major sudden incidents, accidents, and disasters involving Fuzhou: major production safety accidents, accidents involving environmental pollution or ecological damage, public health incidents, public safety incidents, terrorist attacks, traffic accidents, etc. Major natural disasters: mudslides, landslides, floods, fires, etc.;

- Mass incidents with a relatively large impact on the Fuzhou area: mass violent demolitions, demonstrations, rallies, petitioning, etc;

- Speech attacking the Party committee system or government departments;

- News reports, opinion pieces, and all types of city ranking information that affect the reputation of the city;

- Information on all fields that involve [government] officials and government [agencies], such as river regulation, subway construction, traffic management, housing price regulation, medical insurance, culture and education, production safety, urban construction, and city appearance;

- Relevant information on other core work of the municipal Party committee and municipal government.

These general categories of information—about local policies and officials, about sudden “incidents,” about gatherings of people—appear in many procurement notices. Despite the divergence in local officials’ interests, the types of information different localities want to monitor largely echo the ones outlined by the Fuzhou Propaganda Department. In 2018, for instance, the People’s Government of Gansu made clear its “Provincial Government Internet Public Opinion Monitoring Information Service Program” would be used to buoy popular perceptions of individual leaders. The “leadership public opinion” package was to “provide information and data on leaders and other prominent figures, collecting and monitoring public opinion information related to the leadership, so as to understand the public’s views of the leadership in a timely manner and maintain leaders’ good images.”

Authorities hope to keep track of all this information across a number of different online platforms. Many procurement notices describe in detail the desired scope of monitoring, listing the minimum number of sites purchasers want crawled. In 2017, the Lanzhou Public Security Bureau’s Traffic Police sought a system that would monitor social media platforms including Sina Weibo, Tencent Weibo, NetEase Weibo, and Sohu Weibo; major news outlets such as Sina, NetEase, Tencent, Xinhua, Phoenix, People.com.cn; and online forums like Tianya Community, Baidu Post Bar, Renaissance Forum, Kaidi Community, Development Forum, and locally-specific forums. Some procurement notices contain the exact same or very similar requirements, suggesting either that they are responding to specific minimum requirements set by the central government, or that local authorities crib from each others’ procurement notices. In August 2018, the Tibet Autonomous Region High People’s Court stipulated that its system monitor “no fewer than 30,000 websites, no fewer than 3,000 forums, no fewer than 1,000 digital newspapers, mainstream news clients. The frequency of Weibo and WeChat public account collection must reach the minute level, [and] the page analysis accuracy rate must exceed 95%.” In February 2019, the Beijing Urban Management Bureau’s in-house propaganda unit requested exactly the same specs.

It’s not only text-based content that worries authorities. Government agencies also want the ability to monitor audio and video content, either as part of a larger package or as its own project. Officials in the Yanqing District Office of Cybersecurity and Informatization in Beijing put out a procurement notice in 2019 explaining that while “audio and video are widespread on the Internet at present, with a large number of views and great influence,” processing and analyzing such content remains relatively difficult. The notice sought a “system for file collection, voice recognition, and analysis of Chinese and English audio and video from around the world,” as well as software to conduct data mining on what had been collected.

Government buyers hope to purchase monitoring systems that take into account the content many websites personalize based on a user’s profile or geolocation information. The Institute of Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine, for example, sought a system that could use a pool of IP addresses to “simulate real machines and different user attributes . . . improving the quality of data collection by simulating regions, interests, and age groups.”

Officials know they cannot control every single errant Internet post. “The government is targeting people based on their influence and based on the social space they are inhabiting,” says The London School of Economics’ Miller. “It has to prioritize because it has limited resources. . . Instead of focusing on 50,000 retweets, you can focus on the 500 people that have been retweeted a lot, and that’s the way of controlling the message.” The Huaqiao University School of Journalism and Communication, in soliciting bidders for a new “Overseas Chinese New Media Public Opinion Monitoring Service,” outlined its collection requirements for Weibo, Facebook, and Twitter: “analyze the distribution chain of news, discover public opinion tipping points and opinion leaders, and provide data about [posts] that have been transmitted multiple times.” A number of procurement notices evinced authorities’ interest in tracking certain individuals’ posts, including those of “opinion leaders.” The Beijing Federation of Trade Unions wanted 24-hour monitoring of particular netizens to “grasp the trend of how their speech disseminates.” This kind of tracking can happen in bulk, as with the Tianjin Center for Disease Control and Prevention, which hoped to watch “5,000 sensitive Weibo accounts.”

Many government agencies also hope that monitoring technologies can provide early warnings for potentially problematic online developments. In 2018, a “certain work unit” listed the parameters for five different types of early warnings: one based on a large number of re-posts or shares; one for pre-set sensitive keywords; one for posts from “key opinion leaders”; one for websites prone to “frequent outbreaks of public opinion incidents”; and one for anniversaries of specific events, which entailed the system automatically conducting heightened monitoring around “special times,” such as anniversaries related to the banned group Falungong or to the Tiananmen Square massacre. The Liucheng Propaganda Department wanted its system to maintain “blacklists” and “whitelists” and upon finding information online contained in one of the lists, trigger “emergency warning and handling” within 15 minutes to “control public opinion and maintain social stability.” One buyer wanted a system to grade early warnings by degree of severity, evoking a 2014 article in the journal Xuexi, which posited that public opinion incidents could be classified into “ordinary serious incidents, relatively serious incidents, fairly serious incidents, and particularly serious incidents.” Similarly, the Beijing Traffic Police wanted their system to assign a “public opinion level” to each day.

Procurement notices sometimes stipulate a minimum accuracy rate for early warnings, like the Propaganda Department in Beijing’s Shijingshan district, which demanded an accuracy rate of “no lower than 80 percent.” Governments often specify the methods by which they want contractors to reach them for such early warnings, including phone, WeChat, SMS, email, or QQ.

Commercial service providers are not only supposed to send early warnings to their government clients in case of an emergency, but are also responsible for providing continuous reports as a crisis develops, making response recommendations along the way, as in the case of Li Wenliang. In its procurement notice for a public opinion monitoring system, the People’s Government of Gansu province described its desired emergency response measures:

In response to a sudden public opinion [incident], the service project team provides a series of services, such as continuous, real-time dissemination of situation reports; dedicated research and analysis; and crisis management procedures. On the one hand, [the team] tracks the source of relevant information, its transmission path and current status; analyzes and predicts public opinion trends and social psychology; and puts forward professional and scientific public opinion response recommendations. On the other hand, [it] coordinates with crisis response experts who are on standby in order to make good crisis response recommendations. [It] ensures that relevant [government] departments have full control over the occurrence, development, and trends of the incident, and respond calmly. The service provider shall provide no more than 10 crisis response recommendation reports.The Beijing International Horticultural Exhibition Coordination Bureau mandated that its contractor “strengthen” contacts with a range of “key opinion leaders” so that it could offer up a list of no fewer than 20 to help guide public opinion in case of a crisis.

In addition to raising the alarm for an emergency, buyers often want their service providers to submit public opinion reports on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis, plus semi-annual or annual reports analyzing and assessing larger trends. The Beijing Traffic Police estimated that it would need an average of 10 to 15 “sensitive public opinion bulletins” every day.

Officials also demand their day-to-day information collection and monitoring advance at a rapid clip. The Public Security Bureau in Zherong county, Fujian province wanted a system to harvest new posts from monitored sites ideally in under a minute, and in three minutes at longest.

Government agencies hope to harness big data and machine learning technologies to aid in “scientific” decision-making or to predict public opinion trends. In 2019, the Beijing High People’s Court requested an “artificial intelligence big data statistical decision analysis module” that would exploit more than three years of historical data to “help users intelligently research and make scientific decisions.” The system would use big data to

predict the trend, main characteristics, and risks associated with Beijing-related public opinion for a [specific] period of time, and provide corresponding solutions and response strategies . . . When new sensitive information is found, use the historical public opinion database for comparison and analysis, to predict the risks of future public opinion trends . . . Intelligently push [notifications of] current major sensitive cases in other regions of the country, such as ‘vaccine cases,’ and use big data analysis to determine current hot areas of law-related public opinion, giving warnings and recommendations.

Local officials’ go-to monitoring tools may boast new or “scientific” technologies, but they still function within the timeworn tradition of safeguarding the CCP’s rule. China’s leaders “need to know if they’re doing a good job, just from a self-preservation perspective,” says CSIS’s Jude Blanchette. “For reasons that aren't necessarily nefarious, the Party knows there are limited channels of input, so they want to get a full analysis of what the public thinks, but without having to pay the cost of having more open feedback mechanisms.” At the same time, China’s leaders would welcome the ability to know what the public is thinking without the messy reality of their actual speech. In effect, Blanchette says, leaders are asking themselves, “Wouldn't it be great if we don’t have to really allow the public to say what they think, because we have created these AI mechanisms that can tell us if the public is angry?”

* * *

Putting Public Opinion in its Place

Once officials across the country have gathered and digested seas of information on what China’s citizens think, the more critical work of “managing” can begin. Many government agencies aren’t content merely to discover public opinion, they also want it, as the Tongzhou District Public Security Bureau in Beijing put it, “speedily handled.”

Like the phrase “public opinion,” the term procurement notices use for “handling” (处置, chuzhi) carries a political moral charge. “Chuzhi means to put something in the place where it ought to be,” explains Perry Link. “It’s more hands-on” than other words that can also be translated into English as “handle,” and it is sometimes glossed as “disposition” or “dispose.” In most procurement notices we reviewed, “handling” implicitly includes the notion of proactively “guiding” or “channeling” public opinion, which can entail diluting unwanted content by drowning it in unrelated or explicitly pro-government posts.

But “handling” can also mean deleting or blocking information. For the most part, procurement notices employ the term “handle” rather than “delete” or “block.” But a few notices explicitly mention deleting capabilities or processes. The Sichuan branch of the Computer Network Emergency Response Technical Team/Coordination Center of China (CNCERT) wanted the ability to block or delete offending information with “one click.” The Propaganda Department in Liucheng county in Guangxi sought a system that would allow users to “submit blocking tasks according to their handling needs, to achieve the goal of handling public opinion.”

However, not all government entities automatically have the power to expunge information from the Internet. Indeed, the 2016 State Council Notice on “Better Responding to Public Opinion” made a distinction between the myriad local departments expected to establish their own monitoring programs and the relatively few public security or Internet monitoring agencies charged with “investigating and punishing” online speech that threatened “social order or national security.” CNCERT and the Liucheng Propaganda Department are part of the PRC’s formal propaganda apparatus, and so have the authority (and responsibility) to delete information perceived as a threat. By contrast, the State Administration of Taxation told prospective corporate bidders in 2017 that in cases of “major negative public opinion” they would have to help “collect and organize the sources, website links, and other information related to the negative public opinion,” so that the State Administration of Taxation could request that the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission “assist with post deletion.”

Beyond simply removing or obstructing undesirable information, officials want to change the overall tenor of online chatter by injecting their own commentary into the debate. Procurement notices soliciting “Internet comment management systems” portray a series of government buyers who hope that commercial software and personnel can improve the efficiency of this process.

Official sources very rarely acknowledge the existence of online commenting as government practice, but some of the data companies that work for Chinese government bodies openly advertise their comment management systems. For example, the Communist Youth League-affiliated company CYYUN shows images of its online comment management system on its website, as one of its “comprehensive guidance and control products.” It explains that,

Users can send, receive, and handle public opinions through mobile and web terminals; disseminate and popularize some positive opinions, while at the same time correct and clarify some statements that do not conform to the facts, so as to guide the public’s awareness in the correct public opinion direction. At the same time, [the system] can automatically conduct scientific and fair statistics and assessments of the tasks completed by the Internet commenters, effectively reducing assessment workloads and improving fairness.

Only a handful of procurement notices describe online commenting in detail, while a number of others allude to the practice. Some notices specify the number of commenters a vendor should provide, like the one published by the Beijing International Horticultural Exhibition Coordination Bureau, which wanted “no fewer than 10 Internet monitors and Internet commenters.” Or the Chengdu Number Two Hospital, which sought a service provider that would engage “a team of professional Internet commenters with no fewer than 50 people to assist with online responses to public opinion, and provide a list of personnel.” A notice from the Hebei Coal Mine Safety Supervision Bureau discussed Internet commenting as part of a larger PR strategy: “After discovering public opinion information for the first time, quickly establish emergency records and measures, [and] launch online commenting as well as public relations in the media in order to channel the trend of public opinion.”

Government purchasers also seek commercial help to automate commenting. The Lanzhou Traffic Police, in a 2017 procurement notice, outlined the two methods it planned to use to “guide public opinion.” The first, more traditional method would be led by human Internet commenters at the Lanzhou Internet News Center (an agency that is part of the propaganda apparatus). The second would rely on the Eefung company’s proprietary “Eagle” software system, a “smart commenting system” that would “perform semantic recognition and judgment on negative information, controlling the speed of negative information diffusion by using automatic replies, up-voting, etc. to automatically dilute, bury, and suppress negative information.” Such systems, “never work perfectly and have false positives and false negatives,” says Jeffrey Knockel, a research associate at The Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto, “but [the reason] why this one is diabolical is . . . that it doesn’t outright delete content. It hides it by upvoting other content, making it hard to even know if your content was censored, thus granting the system plausible deniability for its mistakes.”

In a similar effort to mechanize parts of the commenting process, the Liucheng Propaganda Department wanted its service provider to supply pre-existing comments, already tagged by topic, which would be reviewed by staff before being entered into a “comment library” software program. To disguise how much of the commenting process would be automated, this software would screen out overly similar comments and ensure the same comment would not be posted twice.

Local governments also seek algorithms to evaluate the work of human commenters themselves. An Internet Commenter evaluation mechanism sought by the Beijing High People’s Court in 2019 would review an Internet Commenter’s posts and award points based on specific criteria. Among them: for any given assignment, only original comments would receive scores—comments containing recycled content would receive zero points; comments only containing three or fewer characters would receive zero points; the more time that had elapsed between task assignment and comment, the fewer points awarded to the comment; for any comment containing specific words alluding to the idea of “Internet commenting,” six points would be deducted and the comment would not be published. Any comments saved by an administrator would get three points.

The Beijing High People’s Court’s notice presents a particularly extreme example of Internet commenting practices. The court’s procurement notice called for a vendor to provide 10,000 different Weibo accounts (or “vests,” in the parlance of the notice) and 20,000 different “vests” on other websites such as Sina, Tencent, and NetEase, from which court-employed Internet Commenters could publish posts. These “vests” were to appear to come from 10 different provinces and 40 different cities around the country, with the ability to be posted from 70,000 different IP addresses that represented 15 different provinces. The comment system, called “The Intelligent Web Review Management System V3.0,” was also supposed to be able to publish 5,000 posts per hour, forward 50,000 comments per day, and support at least 700 people “carrying out Internet comment work in real time” on mobile and desktop platforms. The court was, in effect, seeking a small army of fake social media and other website accounts from which to disseminate propaganda or otherwise “handle” public opinion.

Even taking China’s population size into account, this is an extraordinary degree of online manipulation. “The scale is unusual. That’s a big-scale commenting operation,” says Rachel Stern, Professor of Law and Political Science at Berkeley Law, who researches Chinese courts’ procurement notices. And yet, this seeming anomaly still fits neatly into a larger history of the Beijing High People’s Court, and its longstanding views of media coverage and public opinion. Columbia Law School’s Benjamin L. Liebman, who studies the role of artificial intelligence and big data in the Chinese legal system, says, “This sounds like an extension of what’s long been a practice,” even if it is “at the extreme end of size and scope. 20 years ago, they were focused on relationships with the newspapers. The scale [here] is bigger but it seems like a natural progression.”

Compare this with analogous activity by brand management firms in the United States. In November, The New York Times reported that a firm called FTI Consulting, hired by oil industry groups, created one fake Facebook account to enhance the appearance of grassroots backing for various fossil-fuel energy sources in the U.S. (An FTI employee told the Times that creating the account had been “wrong” and against company policy.) In another example, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission last year fined the company Devumi for selling “fake indicators of social media influence—like Twitter followers, retweets, YouTube subscribers and views, and more.” Even though Devumi was dealing in very large numbers of fake accounts (it controlled some 3.5 million bots and had sold 200 million Twitter followers), its clients were generally only purchasing access to some subset of these, hoping to manufacture an air of online popularity and influence. This is quite different from an organ of the state fabricating netizens to pump out official talking points or to try and bury legitimate public debate—an organ of the state, no less, outside the traditional propaganda apparatus.

The Beijing court’s troll farm highlights how evolving computing capabilities have begun to shift the power of the Internet from citizens to governments. “I used to think, back when I was monitoring Weibo in 2012, that Internet users were outpowering and outspeeding online censors,” says Xiao Qiang, a researcher focused on technology and human rights at the University of California, Berkeley School of Information. “If you think of this as a war, this new arsenal—that the government has and that citizens don’t have—has completely changed the battlefield.” Automated, always-on systems allow “different government agencies, at different levels, in different contexts” to cover far more websites than any one human could, discouraging people from voicing their opinions because they know their speech will quickly be lost in the avalanche of ensuing posts. “It used to be that people would write something good, and it would spread and then be deleted . . . Now, you are writing into a garbage can.”

* * *

‘Communication Confrontation Situation’

The dangers of public opinion, as the Party views them, arise not only from within China, but also from without. To truly ensure that no bad news will reach China’s shores, so goes the thinking of the CCP leadership, the Party-state must permanently “change the conversation at the global level.” Though purchases of systems for domestic monitoring dominate, a number of Chinese government agencies—at the national, provincial, and sometimes even county level—have solicited services to keep tabs on international public opinion as well. In some cases, this is limited to Chinese-language media, but often it includes English and other languages. In 2019, for example, the Beijing Customs Service Center was looking to keep tabs on foreign media from “key countries” and “countries related to the ‘Belt and Road’ strategy,” in at least 60 languages including Chinese, English, French, German, Russian, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, Spanish, Arabic, and others.

Monitoring overseas media, however, presents technical and legal challenges specific to companies based in China. The Yanqing District Office of Cybersecurity and Informatization in Beijing informed potential bidders that any monitoring system they offered “must fully consider [sites] such as YouTube that domestic networks cannot crawl or [from which they cannot] download audio and video.” Multiple notices state that companies are not permitted to collect overseas data by “jumping over the wall,” meaning that they cannot access sites blocked by the PRC’s censorship regime. To comply with this restriction, both the Shijingshan district Propaganda Department in Beijing and the Tibet High People’s court stipulated that a winning provider would need to “possess exclusive technical systems and facilities overseas.” The Gansu People’s Government wanted foreign social media data to be transmitted back to mainland China via “a dedicated line.” These strictures on overseas data collection, if they are actually enforced, presumably limit the number of companies that can successfully bid on certain projects; it is unlikely that a small, less-well-connected company would have access to overseas facilities or a “dedicated line” to legally bypass China’s censorship regime.

International public opinion management also differs from its domestic equivalent because of the comparatively limited repertoire of “handling” measures that can be deployed outside of China. At home, propagandists can simply censor certain online speech, and even government agencies without the authority to delete can apparently establish an army of Internet Commenters to spin a debate or drown out undesirable sentiment. Outside China, its officials can’t simply censor at will, and online debates often prove hard to influence, let alone win.

The Xinhua News Agency, in tacit recognition of this reality, sought in 2017 to “achieve a certain degree of control over [foreign] social media public opinion by influencing the direction of [foreign] opinion leaders’ speech.” The Agency solicited bids to upgrade its “overseas public opinion data analysis system,” the “opinion leader management” component of which would include “opinion leader [database] maintenance, opinion leader analysis, and opinion leader guidance and control.” The system would keep up-to-date records of these “opinion leaders” and automatically classify them according to their estimated influence, tracking what they said about China in order to “promptly discover the opinions of opinion leaders and make timely responses.”

Would these “timely responses” come from official Xinhua accounts or from the kinds of falsified user accounts that the Beijing High People’s Court was buying? The notice doesn’t say. It is possible that Xinhua only intended to engage in online discussion much in the same way a corporate public relations officer might—responding to online complaints or comments from an account clearly associated with their place of employment. Institutions throughout the Party-state, however, employ people to post content anonymously on domestic Chinese platforms. Pro-Publica’s in-depth study of fake and hijacked Twitter accounts and ASPI researchers’ look at Twitter responses to Chinese government content both strongly suggest that China’s government deploys pro-CCP commentators outside China as well.

A different procurement notice, from the Public Security Bureau (PSB) in Tieling city, Liaoning province, was not nearly so circumspect. Looking to buy a “smart Internet-commenting” system, the Tieling PSB wanted to be able to comment on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube from millions of different IP addresses, using thousands of different accounts and even employing automated commenting. All this from a police department in a fifth-tier city. Though it was not looking for anything so sophisticated as identifying international thought leaders and posting targeted responses, the Tieling PSB was still seeking to spam major international platforms with its messages.

China Daily, a state-owned media outlet aimed at foreign audiences, also actively monitors and analyzes public opinion outside of China’s borders. In October 2017, it issued a procurement notice for the construction of what it called a “media electronic sand table,” “a platform that evaluates the effects of the media’s international communications and supports decision-making” to be able to “monitor, evaluate, warn, and intervene in international communications as a whole.” Utilizing big data and technologies such as semantic analysis algorithms, the model would examine global public opinion and China-related public opinion; give early warnings when it detects “sensitive information and events” related to China, China Daily, or other predetermined topics (depending on the urgency, the alert could be delivered by email, text, or phone); make automated recommendations about which topics to cover for international and domestic audiences; and assess and make policy recommendations related to the “overall communication confrontation situation,” namely, “the overall situation of China and the West in the domain of communications.”

In addition to the “sand table,” a system upgrade, and a bevy of research reports, China Daily also wanted a company to build them four new databases: a foreign media encyclopedia, a cache of indexed foreign news articles, a repository of Chinese leaders’ foreign policy speeches, and a “basic database for the media’s international communications capacity-building” to help evaluate the effectiveness of China’s international media efforts. Among the media outlets whose work was to be included in the latter were CGTN, Xinhua, People’s Daily, China Daily, China News Service, CCTV, and China Radio International. Between the “sand table” and the capacity-building database, the China Daily procurement notice prioritized a system that would be able to evaluate how the publications’ coverage is received abroad and how effective it is at convincing foreigners of its message.

International companies do not appear to play a major part in Chinese government agencies’ overseas media monitoring. In its 2017 procurement notice, Xinhua News Agency noted that it relies on third-party big data analysis reports to do its work, and that it hoped to expand cooperation with both domestic and foreign data suppliers “in response to the requirements of senior leaders.” The China Daily procurement notice showed that it paid annual fees to several Western companies (Meltwater, CustomScoop, and quintly) for access to data.

Yet, whether or not international companies do or will play a large role, the Party-state is still determined to conduct “public opinion work” outside of China. Local government agencies of all sizes, from global media conglomerates to county-level propaganda departments, are harnessing the know-how of domestic commercial firms to try and change the conversation abroad.

* * *

The emergence of the public opinion service sector offers a glimpse of what techno-authoritarianism (an oft-cited but under-explained phrase) might actually look like in practice in China: the Party-state’s use of, and reliance on, private technology companies to manage the volatile interaction between ideas, speech, and society.

The cooperation between the state and corporate interests affords a number of benefits to the Party. As described by Leiden University’s Rogier Creemers, private sector dynamism generates new products that are good for China economically “as well as of considerable political utility. Private companies are also not beholden to the same patronage networks and interest groups within the Party in the same way as state-owned enterprises. Yet they do allow for autonomous, often crowd-sourced data-gathering in a manner bypassing potential local interference . . . reducing the ability of grass-roots cadres to deflect or ignore central demands.” Procurement notices themselves describe some of the ways government agencies believe commercially-incubated technologies will allow them to function better, including through “scientific handling” of emergencies, “scientific decision-making,” and “objective” analysis that cuts through prior assumptions. Whether or not big data and digital technologies actually offer better access to the truth is a separate question.

The PRC’s propaganda machinery now depends on commercial enterprises to carry out its mission. Individual government agencies do not have the capacity to undertake constant, fine-grained Internet monitoring all on their own—if they want to know what the public is saying online, they need to enlist the help of outside companies, including those without official ties to the state. The Party, with its increasing influence over businesses of all kinds, clearly feels that outsourcing some of this work poses few risks even if it considers the work itself highly sensitive and consequential. Of course, Chinese authorities have long depended on companies to help keep their own websites and platforms “clean.” But the expansion of commercial “public opinion” monitoring into the organs of government itself draws those companies ever closer to the beating heart of CCP power.