Open Government in China: Bound to Improve, Within Bounds

Written by Jessica Batke,* Julia Breuer, and Matthias Stepan.

Originally published on the China Policy Institute blog.

—

From remarks by the Premier to new guidelines for open government, we’ve been hearing a lot from the Chinese government about its commitment to improving government transparency recently. But given the infamous opacity and top-down nature of Chinese governance, what does this really mean? Our research into the public availability of high-level state documents suggests that Beijing has made good-faith efforts to fulfill the transparency goals it set for itself in 2008, and we should expect similar progress with regard to new initiatives going forward. However, there remains a fundamental tension between the principles of open government and the principles of CCP rule, including differing views of public participation. This tension will likely circumscribe the PRC’s ability to fully embrace the more bottom-up aspects of open governance.

A Push for Better Governance

The Chinese Communist Party has a PR problem. (More specifically, local cadres have a PR problem – citizens are not entirely convinced that local cadres have their best interests at heart.) It has become more important than ever for the CCP to convince its citizens that it is a legitimate ruling party. That is to say, after years of breakneck growth and the attendant pressures on governance structures, the CCP must show, through its responsiveness and concern for citizens’ needs, that it is still a government worth supporting. As part of this attempt to reinforce regime legitimacy, the CCP is working to modernize and professionalize its bureaucracy, clean up its ranks, and streamline administrative mechanisms. All of these steps are part and parcel of this broader Party effort to solidify its image as a “governing” rather than the “revolutionary” party it once was.

Improving government transparency is an important component of these efforts, one which has been in the CCP’s sights for almost a decade. In 2008, Beijing took an important step forward with the implementation of its “Open Government Information Regulations”—even if the “Regulations” did not meet all of the international standards for transparency. The “Regulations” emphasized top-down disclosure of government information, increased availability of this information across physical and digital platforms, and allowed citizens to request non-disclosed information. But while the “Regulations” indeed improved citizen access to information, they largely did not address additional forms of public participation as described by international transparency organizations, such as allowing citizens to monitor and evaluate government activities and providing raw data specifically designed for citizen “reuse.”

In February of this year, Beijing appears to have taken another major step forward, with the “Opinion on Comprehensively Pushing Forward Open Government Work.” Jamie Horsley of the Yale Law School China Center describes the “Opinion” as “executive order on steroids” with measures designed to bulk up pre-existing transparency processes, such as creating “negative lists” that clarify and limit what types of information cannot be disclosed. But perhaps even more importantly, the new “Opinion” stresses the key role that public participation plays in governance (or, more cynically, in preventing unrest) and seeks to improve processes for getting citizen input and promote government sharing of public data. What can we expect from Beijing in terms of these new commitments? Is it really prepared to embrace a more bottom-up model of citizen participation?

A Record of Improved Transparency – On Beijing’s Terms

A look at Beijing’s recent track record suggests that we can expect that it will take at least some of these new commitments seriously. Under the 2008 transparency rubric, Beijing has successfully worked to provide more information to its citizens about government activities and processes. In the eight years since the 2008 “Regulations” were passed, citizens have submitted ever-increasing numbers of information requests to various departments of the Chinese government (though the total number of requests in 2015 was still less than a quarter of the 713,000 Freedom of Information requests filed in the United States the same year). Horsley estimates that perhaps 60 percent of these requests result in government disclosure, and that despite continued difficulties with uneven local implementation or in obtaining certain types information, Chinese citizens have actively used the “Regulations” to broaden notions of what “public information” can mean in China.

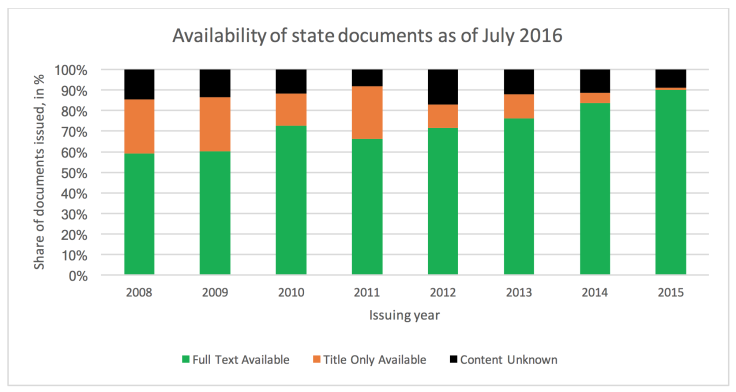

Another indication of how China has fared relative to its 2008 commitments appears in the increasing public availability of official high-level government documents at or near the time of promulgation – meaning that citizens do not need to submit a request for information to get access to them. We catalogued two types of high-level documents issued by the State Council (国发, or guofa, and 国办发, or guobanfa)1 from 2003 to 2015, for a total of more than 1700 documents. We found that the public availability of these documents, including whether a document was directly made available in full-text form or not, has gradually improved over the last eight years since the “Regulations” took effect (Chart 1).

Chart 1: State Documents (issued by the State Council and known as 国发, or guofa, and 国办发, or guobanfa)

This improvement appears to be more than just the result of increased internet use in government work. In the 2000s, for example, a number of guofa and guobanfa were promulgated without any sort of public notification. It was only later—sometimes years later—that the existence of the original “unknown” document became public. This means that while researchers in 2016 may know of a particular document promulgated in, say, 2005, the existence of that document may have been effectively unknown to the public for years if it was only publicly reported in, say, 2009. (Since our study is a retrospective one, our findings only reflect the status of a document during our period of investigation from February 5 to May 15, 2016.) In this way, our data show some mid-2000s documents as being more “available” than they actually were at the time of their promulgation. By contrast, there was only a very small percentage of “unknown” or “title only” documents released in 2014 and 2015, meaning that many more documents are now being made public from the get-go.

Further, it is clear that the 2008 “Regulations” had an immediate retroactive impact on older high-level policy documents. Over half of guofa and guobanfa issued from 2003 to 2007 were not readily available online until just before the “Regulations” came into effect in 2008. It appears that these documents were released in a large batch approximately a month before the law’s May 1, 2008 effective date – meaning that government document availability improved not only moving into the future but also retroactively.

Maxing Out the System, But the System is Part of the Problem

These data support the idea that Beijing takes seriously its commitment to the specific transparency principles it has signed on to. In this regard, the 2016 “Opinion” could well be a significant milestone for open government in China. Given Beijing’s reasonably successful implementation of the last round of open government initiatives, there is reason to think that it will continue to push for effective implementation of even more expansive open government regulations. There are a number of self-imposed constraints and red lines, however, that will ultimately define the boundaries of what will be possible with regard to transparency in China.

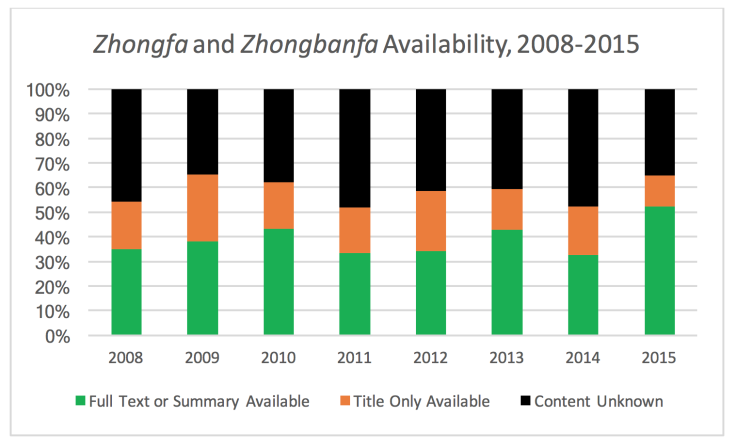

First is the dualistic structure of the Chinese government itself. While open government regulations apply very clearly to state entities, they do not apply in the same way to Party entities. Compared to the State Council documents shown in Chart 1, it is clear that analogous Party documents (issued by the CCP’s Central Committee and known as 中发, or zhongfa, and 中办发, or zhongbanfa) are much less likely to be publicly available (Chart 2). For example, about 90% of the state documents issued in 2015 were available in full-text form, while this was only the case for slightly more than half of Party documents issued the same year. Given that the CCP is still the driving force behind the guiding ideology and policies of the Chinese state, the lack of directly available Party policy documents remains problematic from an open government perspective.

Chart 2: Party documents (issued by the CCP’s Central Committee and known as 中发, or zhongfa, and 中办发, or zhongbanfa)

Second is the fact that, at the most basic level, China’s open government efforts stem from the CCP’s desire to obviate public discontent and remain in power, not necessarily from a desire to support open governance for its own sake. Much like its ongoing anti-corruption campaign, the CCP is willing to push its system as far as it can go to make consequential changes to governance processes—but that system has serious limitations built into it. The CCP continues to fundamentally oppose direct public participation in a range of governance processes and remains congenitally afraid of social organizations outside the auspices of the Party. Based on the PRC’s recent track record with regard to fulfilling its self-imposed transparency initiatives, we should expect that China’s new open governance efforts will produce meaningful results in the coming years. Yet, it is also likely that some of Beijing’s efforts will fall short of international standards, particularly with regard to measures of public participation.

—

Notes

1 These two documents represent the highest-level policy documents that the State Council produces. They comprise not only specific rules and regulations but also more general policy guidance. As such, they are key pieces of information for citizens (and observers) who are interested in the policy priorities and plans of the Chinese state. Guofa are issued by the State Council; guobanfa are issued by the State Council’s General Office.

Additional information about our data:

To compile the data referenced above, we took advantage of the PRC’s very logical official document numbering system, and from February 15 to May 5, 2016, we conducted internet searches for these documents in sequential order. We searched for zhongfa (中发), zhongbanfa (中办发), guofa (国发), and guobanfa (国办发) issued from the beginning of Hu Jintao’s tenure as General Secretary (November 15, 2002) through the current year. For documents that were not listed in central government databases, we only included them in our data set if we could confirm their existence through two additional reliable sources (including sites such as local government websites, Xinhua articles, the Communist Party website, the Peking University law database, and Chinalawinfo.com). There are some documents which are released in full-text form but which do not themselves contain their document ID number. For these documents, we relied on separate sources that confirmed a match between the title of the document and the document ID number. Because of the documents’ sequential numbering identification system, we could be reasonably sure that certain documents do indeed exist, even if they are not publicly available or acknowledged. If we were unable to find the text or even the title of a document that should exist within the document numbering sequence, we counted it as “unknown.” For some Party documents, the full text is not released, but a rather detailed summary is, in which case we coded it as “summary.”

Of course, there are several issues with this collection method that might affect the accuracy of our data set. First, we cannot be completely certain how many documents of each type were released every year – there could be one (or several) “unknown” documents released at the end of any given year which we do not have a way to account for. This is because our collection method relies on sequential ordering and depends on having a “known” document follow an “unknown” document to ensure that the “unknown” document indeed exists. To try and offset this issue, we searched for ten additional documents (beyond the last “known” document) at the end of every year. It is unlikely that we are missing tens of “unknown” documents at the end of every year, but it is possible that we are missing a few in any given year. It is also possible that there are several documents that are indeed publicly available but that we were unable to find; that we did not count several apparently extant documents because we could not confirm their content through reliable sources; or that additional older documents have been released since we stopped compiling the data in May 2016. In any case, the sheer number of documents in our data set (over 2400) suggests that the overall transparency trends we identified would not be substantially altered even if we could address these collection method issues.

—

*This article reflects the personal views of the author and not necessarily the views of the U.S. Government or the Department of State.

Jessica Batke is a research analyst in the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research. There she focuses on modern Chinese society as well as leadership and governance, including cultural, religious, ethnic, media, and political trends. She received her M.A. in East Asian Studies from Stanford University and a B.A. in Linguistics from Pitzer College.

Julia Breuer is a Research Assistant at Ruhr-University Bochum, Faculty of East Asian Studies, International Political Economy of East Asia.

Matthias Stepan is the head of the research programme on Chinese domestic politics at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). He is an expert on policy-making processes and China’s state-party nexus. His research focuses on the changing role of government, and the transformation of China’s social security system. Among his recent publications are “Building the New Socialist Countryside: Tracking Public Policy and Public Opinion Changes in China” published in The China Quarterly, and “The Establishment of China’s New Type Rural Social Insurance Pension: A Process Perspective” in Journal of Current Chinese Affairs. Together with Sebastian Heilmann, he co-edited the essay collection “China’s core executive Leadership styles, structures and processes under Xi Jinping” – the first MERICS Papers on China.